The Seton family at Fyvie Castle

1596 to 1622 - Alexander Seton, First Earl of Dunfermline

In 1588 he was given the title Lord Urquhart, and in 1592 married the Honourable Lilias (or as it was usually written at that date, Lilies) Drummond. Lilias was the second of a family of six daughters and two sons.

The year after Alexander's wedding, in May 29th 1593, at the early age of thirty eight, he was elected President of the Court of Session. In spite of this advancement, it is evident that there was still considerable animosity against him on account of his acknowledged predilection for the Catholic Church. Yet he seems to have been a judge of independence and integrity, and fearlessly asserted the supremacy of the law, even against the King – unusual and dangerous in those subservient times.

A remarkable illustration of his independence of character exists – in anticipation of the death of Queen Elizabeth of England, King James became fearful that her ministers might set aside his right to be her successor in favour of some other claimant; he had the idea of raising a considerable force in order to maintain his title to the English throne. A convention was called to consider the proposition, and although it was supported by a majority of nobles, Seton stoutly resisted it. He pointed out the danger and absurdity of trying to seize the English throne by force, and the inability of Scotland to maintain the required army, and in the end (mainly due to his opposition) the proposition was defeated.

In justice to James, the firmness and independence that Alexander displayed, however much it must have enraged the King at times, never diminished his respect for a subject whom apparently, he delighted to honour. This King, described as 'the wisest fool in Christendom', comes down to us as a man of two parts – a witty, well-read scholar who wrote and debated, and a nervous drivelling idiot, who acted out a part. There were times when it must have required all Alexander's acumen as a lawyer, as well as his dignity as a courtier, to keep well in with such a contradictory character as James.

At the birth of James' eldest son Prince Henry in 1593, Alexander Seton was entrusted with the boy's tuition until he was ten, an honour and an indication of the trust that James placed in him.

The last appearance in records of the President as Lord Urquhart is on December 8th 1597. In 1596 he became the owner of the estate of Fyvie, and he was subsequently honoured with the new title of Lord Fyvie.

When King James' second son, Prince Charles (later Charles I) was born, Alexander was entrusted with his care, and it seems probable that the greater part of his early years were spent at Fyvie. He must have been cared for by both Lilias and Grizel, and is reported as a very frail and sickly child. Just before he was four, his parents requested that he be brought to England, where James had gone to claim his crown of England on Elizabeth's death in 1603 - unfortunately the Prince suffered a serious fever and the King sent one of his own physicians to Fyvie to cure him before Alexander Lord Fyvie accompanied him on his journey south.

Immediately after Queen Elizabeth’s death, Lord Fyvie started his well known correspondence with the English statesman, Robert Cecil, and the steady diplomacy of these two great men did much to smooth out a political situation of great difficulty between two countries more used to flying at one another's throats than working in unison.

In the autumn of 1604, so that King James secured the full benefit of Alexander's legal knowledge and political sagacity, Montrose was persuaded to resign the office of Chancellor –this was then bestowed upon Alexander Lord Fyvie, who had previously been vice-chancellor. After remaining in England a further five months or so, Alexander returned to Scotland in style, and on March 4th 1605 he was advanced to the title of Earl of Dunfermline which had previously only been a title for Royalty.

That summer of 1605 found the Chancellor again an object of animosity on account of his Romish proclivities., and a determined attempt was made to oust him from his office by representing to the King that he had actually approved an unlawful assembly which he subsequently condemned. The King was highly offended but Alexander just forcibly denied it, and James appears to have let the matter drop. From this it would seem that the Chancellor's profession of Protestantism was still a matter more of expediency than conviction.

Alexander's life appears to have been a strenuous and anxious one between his bigoted contemporaries on the one hand and on the other a man of James's temperament, under whom the continuance of Royal favour and the tenure of any office must have been precarious. In private life he was passing through a sorrowful time – he lost his infant son and heir Charles in 1605 to the plague, as well as his young niece, and his wife Grizel died on 6th September 1606, shortly after the birth of her second daughter Lady Jean. She was buried in the vault at Dalgety, leaving her husband to cope with an increased family of daughters, the eldest of whom was then just thirteen years old.

A widower for the second time within six years, Alexander seems to accumulated a considerable amount of wealth through his two marriages. He was left with beautiful jewels and rich dresses from both ladies, and Grizel had assets of land – her estate was valued at just over £17,230 – a large sum for those days.

Alexander however, did not delay in providing his large family of daughters with a stepmother. In 1607, at the age of fifty two, he married his third wife, the Hon. Margaret Hay, who, only fifteen at the date of her marriage, was only one year older than her eldest stepdaughter.

On 16th June 1622, after a brief illness of fourteen days, Alexander died 'with the regret of all who knew him and the love of his country'. His body was embalmed and placed in an oak chest, then conveyed by coach and boat to his beloved Dalgety in Fife. Alexander died a man of considerable wealth.

Lilias Drummond

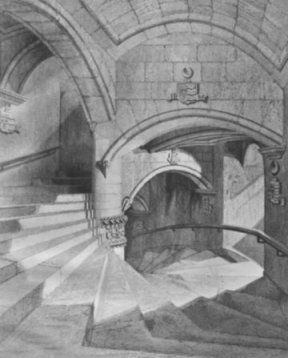

That is history, but we cannot ignore the legend that has grown up around the name of Lilias Drummond. The great stairway at Fyvie Castle winds upwards to terminate abruptly in a window on the left and small room on the right which opens directly onto the stone steps. This room has been called 'the murder room' for generations, and it maybe that the dark panelling conveys a sombre impression which ties in with its sinister name, but there is about it a perceptible atmosphere of gloom and oppression and stains on the wooden floor that are explained as bloodstains.

Tradition maintains that there was once imprisoned in this room 'one of the ladies Dunfermline'. Her name, and her crime, real or imaginary, are lost to us, but some relate that an outraged husband mistreated her; others that she was kept captive by some enemy who in stormy times had raided the Castle; others that she had been guilty of some terrible crime. But the tale runs that she was held there with a guard's arm across the door, while all who made their way up the winding stair in a vain attempt to rescue her, were barbarously slaughtered in her presence and their bodes thrown out of the adjacent window. From the horrors she was forced to witness the lady went mad, and was kept in confinement in another room until her death, which was caused, it was said, by starvation. The room where she is said to have died has long been called 'the ghost room' from the alleged haunting of the unhappy victim.

Another, more explicit haunting tale concerns Dame Lilias Drummond herself. Her husband Alexander was anxious for an heir, and Lilias's inability to produce one, it is said, made Alexander look elsewhere. The closeness of his family and that of his friend, the Master of Rothes, meant that the two families saw a lot of one another – and tradition recounts briefly that he fell in love with his niece Grizel Leslie, and Dame Lilias died.

Within six months of Lilias's death, on October 27th 1601, a marriage contract was drawn up between the Master of Rothes and Alexander, Lord Fyvie, empowering Alexander to marry Grizel Leslie. For some reason, probably because masons were still working on the main part of the building, they spent their wedding night in a more remote room above the Charter Room in the older part of the Castle. Here they heard heavy sighs outside their room, and in the morning they found the name of the dead wife carved into the stone windowsill in letters nearly three inches high – and from within the room the letters were upside down and could only have been carved from outside!

Four centuries later the writing is still there, and it is said that the unhappy Dame Lilias, clad in shimmering green satin, still flits up the wide stairway that her husband built, and along the corridors of the home where she was supplanted by a younger rival.

Some say that the sighting of the 'Green Ladye' bodes evil to the reigning family at Fyvie; others say that she is simply revisiting the home she once loved and where she was foully done to death. It is said too, that in the room where the lady was kept until her death, there is often seen a wan, mysterious, phosphorescent light.

With regard to the tradition of the 'murder room', the period when Dame Lilias lived was comparatively peaceful, since she died before the start of the Civil War, and the Castle is unlikely to have been raided during her residence there. It is even doubtful if the great stairway was finished in her lifetime, and the small room at the top may not have existed unless it was part of the earlier building. So it would seem as if two separate tales have been blended into one, and that the fate of Dame Lilias has been confused with that of another person at another time.

There remains the mystery to this day though, of the name carved in the windowsill. It has been suggested that one of the masons, as a compliment, carried out the work; but if that had been the case would he not have been more decorative – and why in a remote part of the Castle instead of a more prominent place? We shall never know – the origin of the story is as unsubstantial and shadowy as the ghost that has sprung from it, but it remains one of the most arresting ghost stories in Scotland.

1622 to 1672 - Charles Seton, 2nd Earl of Dunfermline

But whatever his early follies, Charles, as second Earl of Dunfermline, nobly sustained the honour of his House in later years, and throughout the troubled years that followed the accession of Charles I, he appears to have acted with sincerity and circumspection. His loyalty may have been confirmed by his marriage to Lady Mary Douglas, daughter of William, seventh Earl of Morton, who was a staunch adherent of the Crown; but from the moment King Charles ascended the throne on 2nd March 1625, England and Scotland entered a period of unrest.

The struggle that was to ensue between Charles I and the Covenanters is a matter of history not entered into here – suffice to say that the King's obstinacy in trying to bring his Scottish subjects in line with his own Episcopal views and with the Church of England, aroused people's bitter antagonism. The riots and battles that accompanied this period did not end until 2nd September 1640, when he was forced to accept a truce.

The second Earl of Dunfermline was reckless and improvident, open-handed and open-hearted, loyal and fearless. At length he was rewarded for his faithfulness by being made a Gentleman of the Bedchamber to the King; and he was also promised in 1646 that on the death of the Keeper of the Privy Purse, he would assume that role., which he did shortly after. This gave him a welcome addition from the Royal exchequer of a yearly pension of one thousand pounds sterling.

The Covenanters had taken a neighbouring Castle – Gight – the previous May, and it is presumed (though no records exist) that Fyvie – an even more important asset - would have been similarly taken. It is recorded that Montrose 'took it (Fyvie) out of the hand of the enemy and occupied it with a garrison of his own men' in October 1644.

Montrose was garrisoned at Fyvie Castle and Argyll, with intelligence received of Montrose's movements and confident of success, rushed in pursuit of his foe. Montrose's own spies or scouts had misled him and told him that Argyll's army had not yet crossed the Grampians – instead he found them camped only two miles from Fyvie! In addition, his own army consisted mostly of Irish auxiliaries - approximately 1500 foot and 50 horse – and his ammunition supply was low. The enemy forces, on the contrary, consisted of some 2500 foot and 1200 well-appointed horse, plus an ample supply of ammunition.

For Montrose the vital thing was to get out of the Castle, so if attacked he would not be trapped. The very fact that the marsh made access to the Castle difficult, also made exit from it difficult and added to his danger. Remember that the Castle stood on a bottle-necked piece of ground surrounded on three sides by the river Ythan, and that (in those days) the space between the river and the south front of the Castle was a marshy swamp. There was therefore only one good way in and also one good way out – the narrow bottle-neck commanded by the oval shaped knoll of Broom Hill, to the East of the Castle.

He moved his men out of the Castle and up to a position on the high ground to the East, only half a mile away from it, but where, if pushed back by advancing forces, he could move north up a wooded valley and not get trapped. A contemporary report says 'He drew up his men on an eminence that overlooked the Castle, the side of which were rough and uneven; and there were besides several dykes and ditches upon it which had been raised by the farmers as a fence to their enclosures and made the appearance of a camp.'

In the ensuing battle, Argyll charged his opponents and started to gain ground, while Montrose's troops were disheartened and some deserted. However, it seems that Montrose's force of character rallied his troops and he counter-attacked. This went on for several days, until, finally the Covenanters retired disheartened, having suffered heavy losses.

The remains of the trenches said to have been dug by Montrose's army can be seen today, but forgotten and untraced in the leafy solitude of Fyvie woods and under the mossy cover of the hillside, lie the bones of many a gallant Scot and merry Irishman who died in that fierce but ineffectual struggle between the Covenanters and the Royalists.

Fyvie does not seem to have been immune from the clash of arms during the years which followed Montrose's brief occupation of the Castle, and meanwhile, the tragedy of Charles I was drawing to a close. In May 1646 he fled to the Scots at Newark; in January 1647 he was delivered by them to the English parliament, who kept him at Holmby House near Northampton. In the June following, the army took him to his Palace at Hampton Court and sought to promote an agreement between King and people on which a secure peace could be established. But Charles haughtily rejected the offers made to him by Cromwell, and appealed to the Parliament through Lord Dunfermline – an interesting document on this was still in existence at Fyvie in 1928:

A true copy of his majesties message sent to the houses of parliament by the Earl of Dunfermline.

I am commanded by his majestie to make known to the houses of parliament

1.that His Majestie went from Holdenby [Holmby] unwillingly.

2.That he desires they will neglect no means for preservation of the honour of the parliament, and the established Lawes of the Land.

3.That they will beleeve nothing that is said or done in his name against the parliament until they send unto Himself, and know the truth of it.

Eighteen months later, on 30th January 1649, Charles was beheaded; subsequently all the loyal followers who had supported him seem to have been in sore straits. Earl of Dunfermline was again faced with major money problems. However, it is probable that he himself was abroad at the time, because immediately following the execution of Charles I, the Earl of Dunfermline was one of the nobles who went to Holland to offer the crown to Charles II.The chosen King, Charles II, showed little alacrity to assume the honours thrust upon him – with the fate of his father upmost in his mind, with a usurper King of England in all but name, and with the Covenanters arbitrarily dictating the terms on which alone they offered him the Sovereignty of Scotland, it was not surprising that he hesitated before renouncing his lazy, irresponsible existence abroad for the one proposed to him, beset with all its trials and dangers.

Montrose, who had sworn passionately to avenge the death of King Charles I, now fought desperately on behalf of his son, but he did not win – he was caught, and hanged in Edinburgh on 21st May 1650. With his death Charles apparently abandoned all hope of enforcing his own terms for the Sovereignty of Scotland, and accepted the terms of his would-be subjects.

On 1st January 1651, Charles was crowned at Scone and the following August at the head of 10,000 men, he suddenly marched on England. Earl of Dunfermline was one of those left behind for the government of Scotland during the King's absence, but the defeat of the Royalist forces at Worcester on 3rd September 1651 soon terminated this administration. The Earl of Dunfermline hurriedly left Edinburgh for Fyvie, but when the Parliament's army arrived in Aberdeen, he moved further into Moray until he could arrange terms of capitulation.

This left Fyvie occupied mainly by women and children, and the chaos in the country was giving increasing cause for alarm. Cromwell's troops marched through the land, destroying crops, ill-treating the inhabitants, stabling their horses in kirks and kirkyards, and billeting their regiments with threats and violence.

With Cromwell's soldiers scouring the neighbourhood, and constant encounters between them and the Royalist troops, there was little space for monotony.

In 1659, Lady Dunfermline died at Fyvie, having apparently managed to spend those troublesome times in peace there, and was taken to the family burial place at Dalgety in Fife. Charles, Lord Dunfermline, survived his wife for about thirteen years, and to the end his finances were in a bad state. After the battle of Worcester, he probably lived as quietly as practicable at Fyvie until the Restoration, when he was sworn a Privy Councillor to the King, and some years later he was appointed an Extraordinary Lord of Session. The various offices he held and the manner in which he discharged his duties, show that he must have been a man of considerable ability.

However, worried to the last day of his life by his inability to meet his debts, Lord Dunfermline died in 1672, after being Laird of Fyvie for half a century.

1622 to 1677 - Alexander Seton, 3rd Earl of Dunfermline, and Tifty Annie

Alexander succeeded his father as third Earl of Dunfermline and Laird of Fyvie, but is said to have died two years later in Edinburgh, at the age of thirty three. However, there is also an account of Alexander being alive at Fyvie in 1676. History is vague on this point, but a tragic tale has come down to us from this period, which throws some light on Alexander's character – he was always depicted as exhibiting a kindly and sympathetic nature.

Back in 1650, a William Smith of Tifty and his wife Helen were mentioned in contemporary writings as having been summoned to the Presbytery for employing unlawful means to cure their sick cattle (the spectre of witchcraft was never far away in those days).

Tifty is a romantic and tragic spot just outside the park gates at Fyvie and the Smiths rented the mill there, although their dwelling house is said to have been the farm higher up the hill. The ruined mill-house may still be seen on the rising bank of a ravine - it stands hidden in enshrouded trees and tangled bushes, and the burn rushes past it.

William had, besides other children, a daughter called Agnes, reputed to have been very beautiful, whose name locally became Nannie, and in poetry since, Annie. According to tradition, one day whilst standing at the door of the mill with her mother, she saw Andrew Lammie (the trumpeter of the young Laird) pass with his master along the road below her home, gallant in all the picturesque trappings of his office, and as handsome a man as she had ever seen.

Various versions of the story in poetry and song have come down to us from this distant past, but suffice to say, the two fell in love, and used to meet and exchange their vows and kisses in the woodland adjoining Annie's home.

But Annie, the beauty of the countryside and well-dowered, was no match for Andrew Lammie who had little to recommend him except his good looks and gallant bearing. Her father William, as miller, was a man of standing and means, who could look higher than a trumpeter for his lovely daughter and forbade her humble romance.

The sorry fate of the unhappy girl and all she suffered at the hands of her irate parents, in what sounds to have been a most unpleasant family circle, has been perpetuated in various ballads which still have strong appeal today.

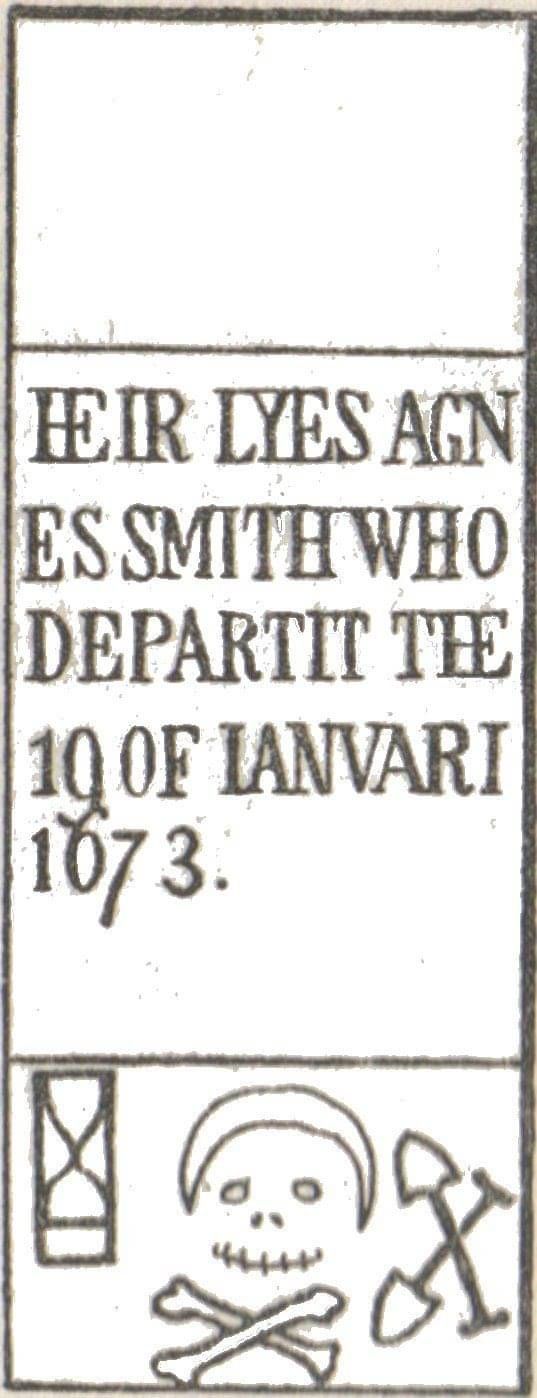

It is recorded that, in January 1673, heart-broken and, according to local tradition, actually killed by ill-treatment, Annie was laid to rest in the kirk-yard of Fyvie. Certain incidents stand out unvaryingly in all versions of the story – the bitter taunts of the entire Smith family in their endeavour to make Annie give up her lover; their cruel ill-treatment of her that resulted in her death; and their defiance of the kindly Laird of Fyvie who, filled with admiration for her beauty, strove to interfere on her behalf.

It is not known whether Andrew Lammie soon followed his love to the grave, or whether he was alive for some years after. There is a tale of the ballard being sung in Edinburgh and one of the audience being Andrew Lammie himself, who became distraught. Certainly it is known that the poet Allan Ramsay, who was born only 13 years after Annie's death, refers to Andrew Lammie, indicating that the ballard was already known and popular in his day. The punishment of the Smith family may have been to find themselves depicted in a most unpleasing light to their contemporaries, and to know how strongly popular resentment was stirred against them.

Agnes Smith, "Tiftie's Annie"

Erected by public subscription, 1859So, through the centuries, Annie sleeps unforgotten beneath the tombstone which is broken in half – the superstitious whisper that this shows the manner in which her death was caused by her cruel brother. And, through the centuries, still on the top of the castle at Fyvie there stands a sandstone figure of Andrew Lammie, forever blowing his trumpet towards Tifty. The site of the Bridge of Skeugh where Annie last met her lover can still be seen today, about 100 yards from where the present stone bridge stands, and a ring of trees is said to still surround and mark the spot where once stood the tree where they met and loved. [Editor's note: this beautiful spot is two minutes walk away from my cottage, and there is indeed a ring of trees that could be the ancestors to the original ones recorded in history].

1677 to 1694 - James Seton, 4th Earl of Dunfermline

In 1682 James asked for the hand of Lady Jean Gordon in marriage; She was the daughter of Lewis, third Marquis of Huntly, and had inherited her mother's beauty. The romantic tale associated with her mother is worth re-telling:

While outlawed and in danger of his life, Lewis had to seek refuge in a cave, and his food was brought to him by Mary Grant, the local Laird's daughter. This lady, who was as fascinating as she was brave, soon won the fugitive's heart. The Presbytery records recount how he seized a minister in the middle of the night and threatened the terrified man that 'he wold pistoll him, yea draw him at ane horse taile' if he refused to marry him instantly to the beautiful Mary Grant. The minister tried to escape, and was dragged back by his hair; with a pistol to his head he was forced to perform the ceremony marrying Lewis to Mary.

So, on July 6th 1682, James married Lady Jean and the following year he was busy preparing Fyvie for occupation by his young bride. The Castle must have badly needed renovating after the Civil Wars, and he carried out many improvements, some of which can be seen today – for example, the fine plasterwork ceiling in what is now called the Morning Room, but was originally the Great Hall of the castle.

However, political storm clouds were again gathering on the horizon, and James was to forfeit all that he held dear in a lost cause, and for a thankless Sovereign.

In February 1685 the Duke of York succeeded Charles II as James II of England and VII of Scotland. His reign was brief and he fled from England at the Revolution in 1688, dragging with him to ruin the faithful adherents who were to sacrifice all on his behalf.

However, things did not continue in the way they had started – James favoured Roman Catholics over others and placed them in favoured positions within his Court and government. This did not go down well with a lot of Scots, but he still had friends – particularly the Viscount Dundee, who diligently went about increasing the number of adherents to James' cause. One of these, true to the loyalty to his lawful Sovereign for which his ancestors had always been known, was James, Lord Dunfermline.

'Bonnie Dundee', as the Viscount was known, started hostilities against General Mackay and the Revolutionary forces without waiting for a commission or funds that James had promised him – James had taken himself off to Ireland.

Tradition is strong, though no written proof has survived, that during this time (1689) Dundee visited Fyvie Castle, where he and Lord Dunfermline planned the campaign they were about to pursue against the rebels.

So, still believing in the Sovereign for whom he was risking life and limb, Lord Dunfermline fought on gallantly with Dundee and others, in a losing cause. He continued to share the touching faith of Dundee, that James would return to place himself at the head of his adherents, instead of skulking in Ireland.

On 27th July 1689, at the Battle of Killiekrankie, just when the rout of MacKay's forces was ensured, the triumph of the Royalists was turned to tragedy. Dundee was hit by a musket ball – it was recorded two days after the battle that he had been shot in the head, although various other accounts also remain. Lord Dunfermline it is recounted, was with him till the last, having miraculously escaped any injury himself.

News of the Battle of Kiliekrankie was carried to James in Ireland and the letters were probably signed by Lord Dunfermline, as the most prominent surviving Chief attached to the Stuart cause. The King however, then heaped yet another indignity on James, - we are told that 'Lord Dunfermline's social position and military reputation were such that after the death of Dundee he would have received the command, except for the weakness of the King who decided in favour of Colonel Cannon, who assumed the command of the Jacobite army and proved himself incompetent.'

Despite the overall success of his adherents at the Battle of Killiekrankie, James continued to absent himself from the scene of action, and his loyal followers became more and more filled with despair at his despicable desertion of them. One of his followers, Lord Melfort, writing on October 20th 1689, remarks sadly:

'The King's friends, who have been in anxious expectation of him all this summer, will be tired out by imprisonment, fines, processes, plunderings, and what is worse, have an ill opinion of the King's conduct, and despair that ever they shall be relieved; and so turn in to where they may be covered from the violence of that tempest they are threatened with.

The remainder of the party in Scotland, already almost ruined by delays, will be quite pulled up by the roots, and the usurpation settled, that it will be most difficult to shake it.'

This prediction was to prove correct, and Lord Dunfermline was among those who paid the utmost penalty for his loyalty. Outlawed by Parliament in 1690, with everything he owned forfeited, he followed the fugitive King to France, where he died in abject poverty.

When James, Earl of Dunfermline, was found guilty of High Treason on 14th July 1690, all his estate passed to the Crown to be disposed of as the King saw fit. For forty three years after their forfeiture, the Castle and estate of Fyvie remained Crown property, until they were acquired by William Gordon, second Earl of Aberdeen.